|

The month of April has flown by, and now score sheets are due. Remember to submit yours by May 1st at midnight PST in order to qualify for the 2017 Freezer Challenge. Misplaced the email with your personalized link to your score sheet? No problem!

Good luck, and thank you all for participating in the inaugural North American Laboratory Freezer Challenge!

1 Comment

As part of the Freezer Challenge we've challenged you to try room temperature sample storage for nucleic acids. Before concluding that it's too difficult or just impossible, take a listen to this NPR segment to learn about the tardigrade, an organism that can live without water for decades. And for the latest findings about tardigrades, check out this article.

You've probably noticed at the end of the score sheet we've asked quite a few questions about the number of cold storage units you have, the types of samples stored in them, and generally how you store your samples. Have you wondered why we're asking so many questions? The data you provide will help us:

This information will help us educate other researchers about current standards. And we will use the data we collect to provide the EPA with valuable insights needed to further the ENERGY STAR effort for lab freezers and refrigerators. So if you haven't yet completed the Data Gathering section of the score sheet, give it a try this week. Any information you provide will be extremely valuable! One of the most difficult aspects of the Freezer Challenge involves samples. All those samples. Hundreds, sometimes thousands, of samples shoved in the back of refrigerators and freezers. Whose initials are those? No idea. Does that say 1997 on the box? Ummm... Inventorying samples can be tough - especially when the samples you're trying to inventory belong to people who have long since left the lab - and it can be tedious work. Even when it means extra points on the Freezer Challenge, it can be tempting to skip the inventory questions altogether. So why bother? Here are a few of our favorite reasons to put on some tunes and settle in for a few days of sample inventorying:

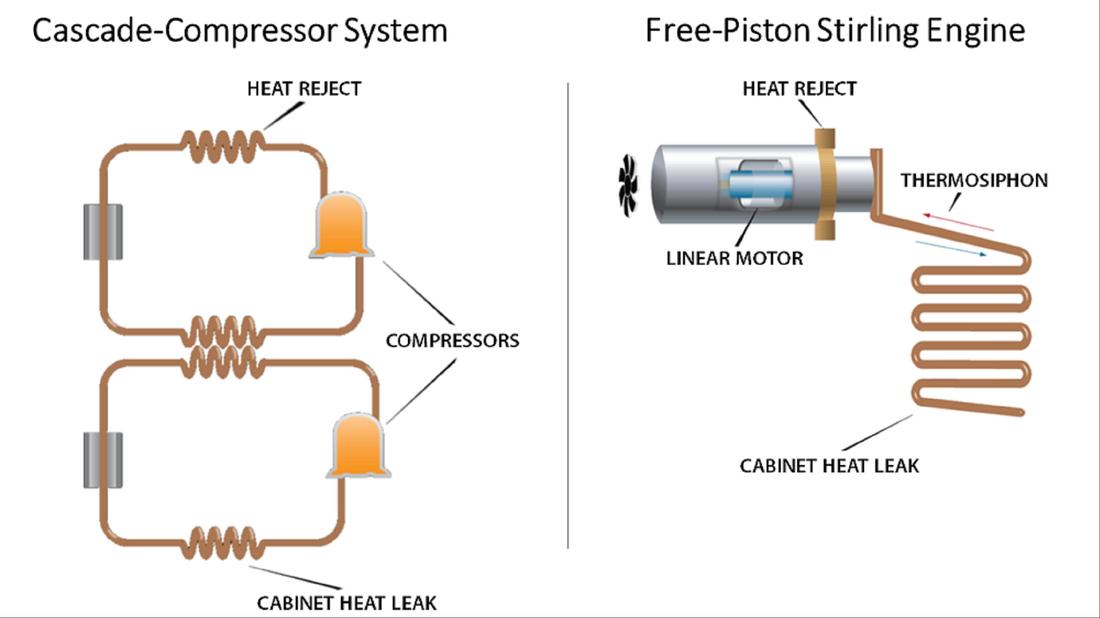

Happy tidying! And don't forget to share pics of your oldest samples on #FreezerChallenge2017! by David Berchowitz PhD, Founder and CTO of Stirling Ultracold Due to the importance of preserving high-value specimens for biological research, ultra-low temperature (ULT, -80°C) freezers are a mission-critical technology for today’s life science, pharmaceutical, and hospital research laboratories. And yet the cooling technology that enables ULT storage is not well understood by most of the people who use it every day. This may have something to do with the fact that, for decades, it was correctly assumed that all ULT freezers used the same mechanical cooling technology. Not until the 2009 introduction of the Stirling engine technology, with its free-piston engine, did laboratories and biorepositories have a viable alternative to compressor-based ULT cooling technology. The Stirling engine concept, which traces its roots back to the 1816 invention of Scottish pastor Robert Stirling, is widely known for its inherent simplicity and efficiency. For many years, this technology has been refined, advanced, and used in multiple applications, including instrument cooling on a NASA satellite that has been in geocentric orbit for over 15 years. Understanding ULT Technology Basics With a differentiated alternative to cascade-compressor freezer systems now available to the research community, we think it’s particularly important that buyers and users understand ULT technology basics. Let’s start by looking at both cooling technologies and the key differences between them . . . Standard Cascade-Compressor Systems: As shown in the diagram below, left side, cascade-cascade compressor cooling systems use two compressors in a cascade arrangement where one compressor cooling loop, the first stage, operates between ambient and an intermediate temperature, and a second stage compressor loop operates between the intermediate temperature and the freezer cabinet. The system evaporator is a copper tube that surrounds the internal cabinet volume, while the condenser is typically a forced air finned tube construction. In addition, there are expansion devices, including capillary tubes, oil separators and dryers typically in the circuits. The Free-Piston Stirling Engine: Unlike cascade systems with two compressors and cooling loops, the free-piston Stirling engine (diagram below, right side) uses only two reciprocating components to provide cooling, and a thermosiphon, which uses gravity to help circulate natural refrigerant around the cabinet interior without a mechanical pump. In contrast to standard cascade systems that regulate temperatures by switching compressors on and off, the Stirling engine’s linear motor system continuously modulates cooling capacity by controlling the stroke of a single free piston. Balancing ULT Energy-Efficiency with Reliable Performance The most well-known benefit of Robert Stirling’s engine was recently observed by Bill Nye the Science Guy when he noted, “The extraordinary thing about Stirling engines is they're so efficient!” By combining this inherent efficiency with advanced technological refinements, a Stirling engine ULT uses 70-75% less energy than comparable, standard compressor-based models*. While improvements in ULT efficiency and sustainability are important on their own merits, we believe these benefits should always support or enhance the reliability of critical cooling systems that preserve valuable samples for research. The Stirling innovation delivers several reliability advantages that address well-known failures associated with legacy technologies used in most ULT freezers. To understand this, let’s take a more in-depth look at the free-piston Stirling engine design . . . First, a simple mechanism is intrinsically less prone to failure than more complex mechanisms. The free-piston Stirling engine has only two moving parts, and there are no moving parts in the thermosiphon. In addition, the moving piston experiences no mechanical wear because it’s supported on gas bearings—similar to a puck gliding on an air hockey table. This eliminates physical contact that causes friction, heat, and wear during mechanical operation. The gas bearings also eliminate the need for any oil, which can clog up the system and lead to mechanic failure. With no valves in the system, the Stirling engine eliminates yet another mechanical component that can fail. The linear motor in the engine controls the stroke of the piston to continuously modulate and change temperature, without stop-start cycles that generate electrical and mechanical stress in compressor-based systems. This not only makes the Stirling engine 100% adaptive, but also eliminates current peaks from on-off surge currents. Finally, the simplified mechanism and sealed construction of the Stirling engine, require very little preventive maintenance to keep the cooling system operating at optimum levels throughout its life. If you would like a more in-depth understanding of how advanced ULT technology can reduce your energy consumption, while also improving reliability and sample safety, please sign up to attend our Freezer Challenge Webinar , presented by Stirling Ultracold’s Director of Quality, Chuck Stout on Thursday, April 13th at 1 pm. Miss the webinar? Listen to it here! * Comparison of SU780XLE energy use data (independently tested using the ENERGY STAR® Final Test Method) with “baseline” ULT energy consumption field data obtained through the U.S. DOE Better Buildings Alliance report, Field Demonstration of High-Efficiency Ultra-Low-Temperature Laboratory Freezers (2014). |

Archives

May 2021

Categories |

The Freezer Challenge is a program coordinated by the non-profit organizations

My Green Lab® and the International Institute for Sustainable Laboratories, and sponsored by various companies with an interest in promoting the most energy efficient cold storage options.

My Green Lab® and the International Institute for Sustainable Laboratories, and sponsored by various companies with an interest in promoting the most energy efficient cold storage options.

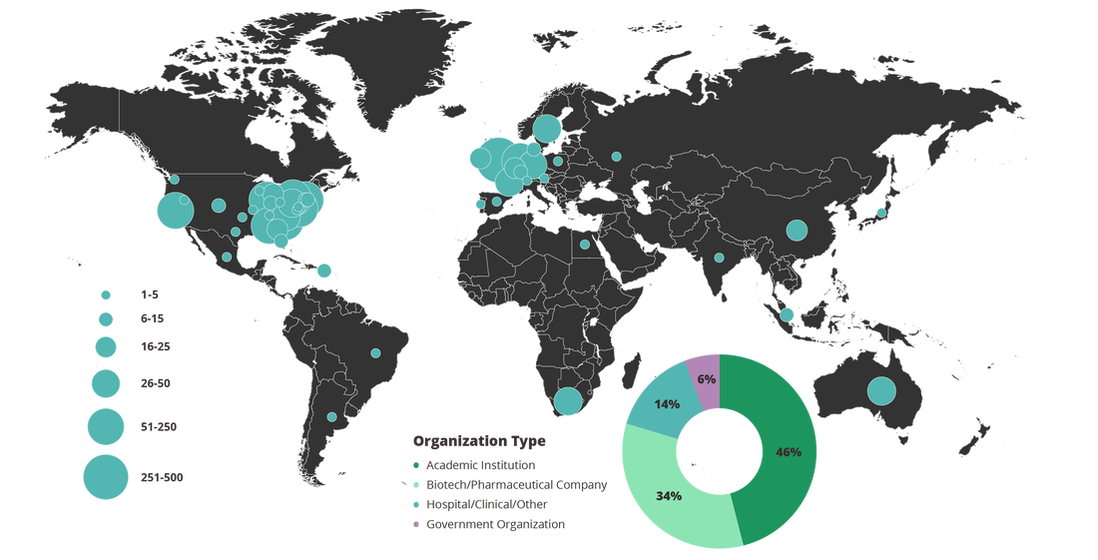

Global Reach of the 2023 International Laboratory Freezer Challenge

RSS Feed

RSS Feed